Spreadsheet calculations

Today we will start digging into use of formulas and functions in Excel. We'll also learn to nest functions, which means to use the output of one function as the input for another, using the example of calculating the mean of measurements from a circular variable (i.e. directions).

Additionally, we will learn about relative and absolute cell references, and how to use them to make complex, repetitive calculations easier.

Cell formulas

Download this file and save it to OneDrive (or your H drive, if OneDrive isn't behaving itself).

Formulas are entries in cells that perform some sort of operation. Cell formulas start with an = followed by cell references, arithmetic operators, or functions - we used them to calculate random numbers earlier this semester, so you already have a little experience with them.

Functions are mini programs built in to Excel that return a value. We have used these too, when we used =now() to return the system time, which we used as the seed for our random number generator.

But, what we have done so far is just the tip of the iceberg - formulas and functions are the primary reason to use Excel rather than a database management system, and we will be using them extensively for the rest of the semester. Today you will learn a little more about how they work, and how you can use combine them together to do complex computations in a single cell.

We will use the example of mutation-selection balance to begin to learn about how to do calculations in Excel.

Background: mutation-selection balance

Genetic diseases can be horrific things - they cause terrible suffering, which is only made worse by the fact that they are passed on from parent to offspring. Most genetic diseases are caused by loss of function mutations that disable a gene that otherwise would perform a crucial function in the body. Loss of function mutations are usually recessive, meaning that a heterozygote does not express the disease (if you recall from Biol 212 or Biol 352, a heterozygote has two different alleles, in this case the disease-causing allele and a normal allele). If we assign the letter B to the normal allele and b to the disease-causing allele, then only bb homozygotes will express the disease, but heterozygotes (Bb) may be no different from BB homozygotes. Heterozygotes that do not express the disease are carriers, because they have the b allele, and will often pass it on to their offspring without even knowing they carry it.

When recessive alleles are rare most copies will be in heterozygotes. This greatly reduces the effectiveness of natural selection in removing the allele from the population, since selection acts on phenotypes (i.e. the organism's appearance or function), not genotypes (i.e. the alleles they carry). Even an allele that is always fatal in childhood, such that disease sufferers never pass on the gene to offspring of their own, is not selected against in the heterozygote carriers.

When the frequency of the allele gets low enough selection becomes so ineffective at removing the deleterious recessive alleles that mutations restore the disease to the population as quickly as natural selection removes it. At this point the allele has reached mutation-selection balance - mutation-selection balance is a stable equilibrium that can persist indefinitely.

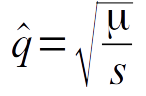

Mutation-selection balance is theoretically expected to occur at:

where  is the expected equilibrium frequency of the b

allele, μ is the mutation rate (i.e. the probability of a mutation occurring at a particular gene locus per unit

time), and s is the selection coefficient (i.e. the relative reduction in reproductive success that occurs due

to the disease-causing allele when it is expressed in homozygotes). The frequency of b is defined as the

proportion of the alleles in the population that are b alleles.

is the expected equilibrium frequency of the b

allele, μ is the mutation rate (i.e. the probability of a mutation occurring at a particular gene locus per unit

time), and s is the selection coefficient (i.e. the relative reduction in reproductive success that occurs due

to the disease-causing allele when it is expressed in homozygotes). The frequency of b is defined as the

proportion of the alleles in the population that are b alleles.

Mutation rates vary, but the estimates that are usually used to predict mutation-selection balance fall between 1x10-4 and 1x10-6 - that is, 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 1,000,000. The selection coefficient also varies a lot depending on the disease, but one that kills all bb homozygotes in childhood would have a selection coefficient of 1 (or 100% reduction in reproduction). Diseases that are not fatal, or that kill later in life (often after bb homozygotes have had offspring already, before realizing they are sick) will have a much smaller selection coefficient, closer to 0.

If we want to understand what kind of allele frequencies to expect for recessive genetic diseases under

mutation-selection balance, we would need to calculate  for

various combinations of μ and s. This would be cumbersome to do one set of values at a time, but by using cell

references in Excel we can do them quickly and easily using formulas with cell references.

for

various combinations of μ and s. This would be cumbersome to do one set of values at a time, but by using cell

references in Excel we can do them quickly and easily using formulas with cell references.

There are two types of cell reference, relative and absolute.

Relative cell references in cell formulas

A. Open the file you just downloaded, and switch to the tab called Cell references.

You'll see that I already laid out a matrix with mutation rates ranging from the low end of expected values

(1x10-6) to the high end (1x10-4) as row labels in column B, and selection differentials

ranging from 0.1 (which is a 10% reduction in reproductive output) to 1 (which is 100% reduction in reproductive

output) as column labels in row 5.

Cell references are combinations of column letters and row numbers, which can be used in cell formulas. As an example:

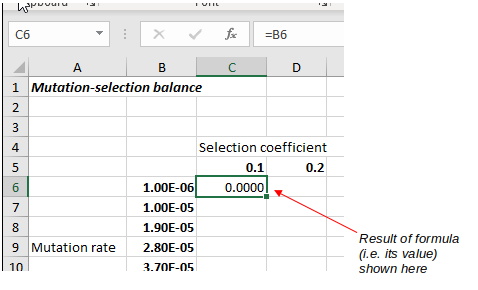

- Select cell C6

- Type =b6

- Hit the ENTER key

You should now see that the value of cell B6, 1.00E-06, is showing in cell C6 as 0.000001 - this is the same number without the scientific notation (note that Excel is not case sensitive, but it does convert lowercase to uppercase letters in cell references - meaning, it accepts the lower-case b in the cell reference as equivalent to B, but it converts the lower case to upper case automatically).

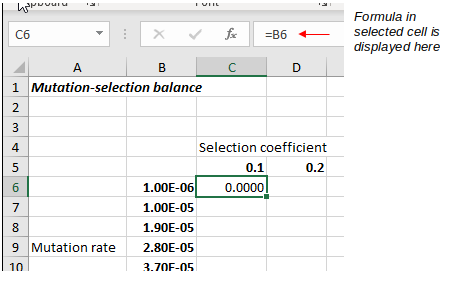

When you hit the ENTER key the selection moved down one row, so select C6 again so you can see what happened -

you'll see that when a formula is entered the result of the formula is displayed in the spreadsheet, but the formula itself is displayed in the formula bar

is displayed in the spreadsheet, but the formula itself is displayed in the formula bar .

.

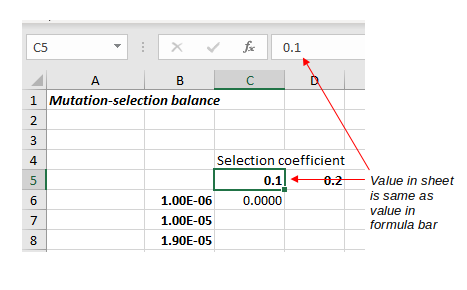

When a cell only contains data the display in the spreadsheet and the formula bar are the

same - if you select cell C5 you'll see that

the value 0.1 is displayed both in the spreadsheet and in the formula bar, so C5 just contains the number 0.1.

- if you select cell C5 you'll see that

the value 0.1 is displayed both in the spreadsheet and in the formula bar, so C5 just contains the number 0.1.

Back to cell C6 - the reference to B6 in this formula is a relative reference. A relative reference is interpreted relative to the cell that the formula is in - Excel interprets the reference B6 as saying "the cell in the same row as this formula, but one column to the left".

B. This is not yet the calculation we need to do, so let's get a little closer to it with this next step.

To calculate the equilibrium frequency for b we need to divide the mutation rate in B6 by the selection coefficient in C5. To do this we need to edit the cell formula we have already entered.

To edit the cell formula:

- Select cell C6

- Click in the formula bar, or double-clicking cell C6 - in either case, the cell is put in edit mode. In edit mode the cell formula shows in the worksheet instead of its value, with any cell references color-coded to match highlighting around the referenced cell (that is, both the B6 reference in the formula and the border around cell B6 on the worksheet will be the same color)

- Change the cell formula to: =b6/c5 (note that when you type c5 as a

reference it highlights the cell it refers to, which helps you ensure you're using the right cell in your

calculation)

- Hit ENTER

You should now have the ratio of the mutation rate from row 6 to the selection coefficient from column C in cell C6 - the value will show as 0.0000 because of the formatting on the cell, but the value is actuall 1 x 10-5, or 0.00001. Just like the reference to B6, the C5 reference is relative, so Excel is interpreting it as "the cell one row above but in the same column as this formula".

C. Because Excel interprets relative references relative to the position of the formula, when we copy and paste a cell with this formula to a different cell it will use the cell immediately to the left and above to do the calculations, rather than continuing to point specifically to cells B6 and C5.

This is a good time to be clear about what is meant by Selecting, Copying and Pasting a cell.

A cell can be selected by:

- Left-clicking a cell once

- Moving to the cell using the arrow keys from another selected cell

- For a range of cells that are touching on an edge: by left-clicking once in a cell and dragging across the cell range

Double-clicking enters edit mode, and a cell that is in edit mode cannot be copied. If you enter edit mode accidentally hit ENTER or click the red x to the left of the formula bar to get out of edit mode.

Once the cells you want to copy are selected you can copy the cells by:

- Right-clicking the selected cell (or anywhere in a selected range of cells) and choosing "Copy" from the pop-up menu.

- Using the keyboard combination CTRL+C (that is, hold down the CTRL key and hit C)

- Clicking the "Copy" button

in the button bar in the left end of the "Home" tab.

Pasting a copied cell is done by selecting the cell that will be the destination (if a range of cells were copied then selecting the upper-left corner of the destination range is sufficient), and then:

- Right-clicking and selecting "Paste" from the pop-up menu.

- Using the keyboard combination CTRL+V

- Clicking the "Paste" button

in the button bar in the left end of the "Home" tab.

The fill handle has the same effect as copy/paste for cell formulas - once a formula is entered in a cell you can use the fill handle to copy it to adjacent cells above or below, or left or right of the current cell.

Okay, with the meaning of select, copy, and paste clarified:

- Select cell C6

- Copy it

- Select cell D6

- Paste the copied cell to cell D6

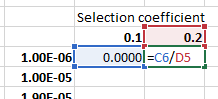

Activate the cell for editing - Excel color codes the cell references, and matches them with highlighting around the cells referred to. You'll see this:

Because the formula in D6 is one column over from where it was originally entered you should see that the formula in cell D6 is now pointing to different cells - it's pointing to the cell above it (the selection coefficient of 0.2) and to the left of it (the μ/s calculation in C6). Since the references were relative to the location of the formula Excel updated the column letters for both of them - this was a good thing for the selection coefficient, but a bad thing for the mutation rate since the formula no longer points to it.

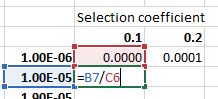

Let's do the same thing again, but this time copy C6 and paste it to C7 - you'll see a cell value of 1.00, which is clearly wrong (we don't expect the frequency to go to 100%), and if you put the cell in edit mode you'll see:

We have a similar problem as before, this time with the row number in the second reference - copying and pasting the formula to the next row down updated the row number for the first reference so that it points to the mutation rate in the same row that the formula is in (good), but also moved the row number for the second reference so that it's no longer pointing to the selection coefficient for the column it's in (bad).

What we want is for the first reference to always point to a mutation rate in column B but let it update the row as needed, and for the second reference to always point to a selection coefficient in row 5 but let it update the column as needed.

To make the cell formulas work this way we need to use absolute references.

Absolute cell references

Absolute references point to a particular row, column, or cell in a way that does not depend on the location of the formula - thus, absolute references stay the same if you copy and paste the formula to a different location. Absolute references are created by placing a $ in front of the column letter, row number, or both. Where you put the dollar sign depends on what you are trying to do in your formula.

A. To make the cell in C6 always point to column B in the first reference, and row 5 in the second:

- Double-click C6 to enable editing

- Change the formula to read =$b6/c$5 and hit ENTER

The cell value for C6 hasn't changed - there's no difference between a relative cell reference and an absolute cell reference until you copy and paste the cell someplace else.

Now that you have the formula you want in C6, copy and paste C6 to the rest of the cells in the matrix - that is:

- Copy cell C6

- Select cells C6 through L17

- Paste the selected cell - pasting a single cell to a range causes it to be duplicated into every cell of the selected range (it wasn't technically necessary to paste into C6, but it's easier to select an entire rectangular range than to leave one cell out of it)

This will put the cell formula in every cell of the matrix, and all of them will be pointing to the correct values in column B and row 5.

B. This is not yet the final calculation of equilibrium allele frequency, though - to get that we need the square root of these ratios of mutation rate to selection coefficients.

We will use the sqrt() function to do this calculation:

- Double-click C6 to enable editing

- Change the formula to read =sqrt($B6/C$5)

The value should now show as 0.0032, which is the expected equilibrium allele frequency for an allele with a selection coefficient of 0.1 and a mutation rate of 1x10-6.

Remember that functions are little mini programs that perform an operation, based on the arguments we provide, and return a value - the value returned by the function is what is shown as the cell value.

The sqrt() function is a simple one, which takes a numeric value as its single argument and returns the square root of that number. We can use the output of our calculation of mutation rate by seleciton coefficient as the input to sqrt() - that is, since we used $B6/C$5 as the argument to sqrt() we do the division first, and then pass the result to the sqrt() function as its argument, and sqrt() calculates the square root of the value.

The formula is complete now in cell C6, so copy and paste C6 to the rest of the cells in the matrix, and you'll get the expected allele frequencies for all of the combinations of mutation rate and selection coefficient.

Hopefully you can see that using cell formulas and cell references not only saves a lot of time, it is much less error-prone than doing the calculations by hand - you only need to enter the formula correctly once and then copy/paste it to the cells needed to complete the calculations.

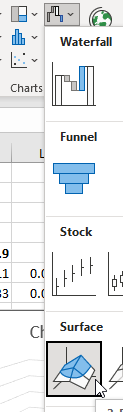

C. We now have a matrix of equilibrium allele frequencies to interpret. A good way to help us interpret a large number of numeric values is to graph them, and a good graph type for a matrix like this is a surface plot.

- Select cells B5 through L17 - this is all of the calculations, as well as all the mutation rate and selection coefficient values

- Select the Insert tab, and then find the Waterfall, Funnell, Surface, Stock or Radar chart button and select

a surface chart (this one

)

)

You should now have a 3D surface chart, with mutation rate and selection coefficient on the two axes on the base (x and y), and the equilibrium allele frequencies that you calculated on the vertical axis (z). You should see that the combination of a high mutation rate and low selection coefficient result in the highest allele frequency, and the combination of low mutation rate and high selection coefficient result in the lowest allele frequency.

Change the title to "Equilibrium allele frequencies", and add axis titles as Mutation rate, Selection coefficient, and Allele frequency (the numbers are really different for the axes, you should be able to tell which is which based on the numbers in the axis tick labels).

D. A good way to put the allele frequencies into context is to calculate the expected frequency of disease from them. Since the disease only occurs in homozygotes two of the disease causing alleles would need to come together to cause the disease - if the allele frequency is q then the probability that two randomly selected alleles from the population will both be disease causing is q x q, or q2.

We'll just do this calculation for the highest expected allele frequency, which is in cell C17, and the lowest expected allele frequency, which is in cell L6:

- In cell A21 enter the label "High frequency of disease" - this will be too wide for the column width, but if

you hit the "Wrap text" button

the row

height will increase and the text will wrap around so you can see it all.

the row

height will increase and the text will wrap around so you can see it all. - In cell B21 enter the formula =c17^2

- In cell A22 enter the label "Low frequency of disease", and wrap the text.

- In cell B22 enter the formula =L6^2

The caret symbol, ^, is used for exponents (this is what we could have used to take the square root of the ratio of mutation rate to selection differential, since ^0.5 is the same thing as sqrt()).

This tells us that the frequency of a disease that only reduces reproductive output by 10%, with a mutation rate on the high end of normal, would be 1.00E-03, or 1 in 1000 births.

At the other end of the spectrum, with 100% reduction in reproduction and a low mutation rate the frequency of disease would be 0.0012, which is 1.00E-06, or 1 in 1,000,000 births.

But, none of the combinations of selection coefficient and mutation rate have an expected allele frequency of 0, so we don't expect selection to ever completely eliminate genetic diseases.

Nesting functions

Nesting functions refers to using one function's output as the input for another. Nesting functions greatly increases the sophistication of calculations that can be done in Excel, since we are able to use nested functions to do things that are not already built in to Excel.

We just used the result of a calculation as the input to a function, and nesting functions is no different. We just need to make sure that the output that the internal function will produce is acceptable as input to the external function.

To learn how to nest functions in Excel we will turn to data that represents measurements on a circular scale. Circular variables are continuous numbers that repeat, rather than extending to positive and/or negative infinity - examples include directions (measured in degrees or radians), days of the year, and time of day. In each case there is an arbitrary starting point (due north for directions, January 1 for days of the year, and midnight for time of day), and measurements increase until they reach a maximum (360 degrees, December 31, midnight) and then they start again.

We briefly introduce circular variables in Biol 215 (you may recall) - we define what they are and point out that variables measured on a circular scale require special mathematical treatment. To refresh your memory, consider the example of direction data.

Direction data as a circular variable

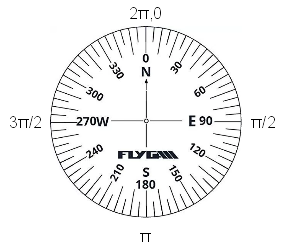

Directions are (relatively) simple circular variables to work with because they are recorded as angles, which are easy to apply the needed trigonometric functions to. Due north is at 0 degrees, and numbers increase clockwise - due East is at 90 degrees, due South is at 180 degrees, and due west is at 270 degrees. The numbers increase to 360, which is the same as 0 degrees - thus, north is actually both 360 and 0 degrees.

A classic example of directional data in biology would be data on movement directions in animals. Pigeons, for example, have a sense of direction such that if we covered the eyes of domestic pigeons, drove due south and released them we expect they would fly north toward home. This would give us directions that are clustered around 0/360 degrees, but because some of the directions are slightly to the west of north (big numbers, near 360) and others are slightly to the east (small numbers, close to 0) their simple average is near 180 degrees, in exactly the wrong direction - you can see this problem in the graph simulating circular data with an average near 0 (clicking "Randomize" gives you a new set of randomly generated directions). We will learn how to calculate average directions correctly to avoid this problem.

Doing math on a circular variable

Now that we understand the problem to be solved, let's see how we will solve it.

A. Switch to the blank worksheet called "Nesting functions". Then do the following:

- Enter the label "Directions" in cell A1

- In cells A2 through A5 enter the numbers 345, 350, 1, and 10 (one direction per row)

- In cell A7 type "Simple average"

- In cell A8 calculate the average of these numbers with the formula: =average(a2:a5)

Averaging the directions gives you a very wrong answer for the mean of 176.5 - nearly due south, which is about as wrong as possible.

The solution to this problem is to convert directions into vector components, average the components, and then convert the average of the components back to an average direction.

Converting directions into components requires a little basic trigonometry - to review:

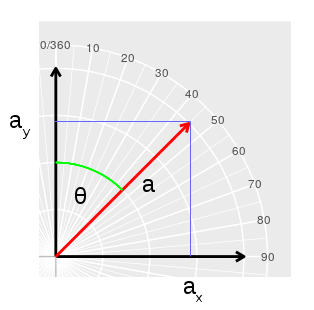

We can graph a direction equal to the angle θ as a line segment (the red line a) starting at the center of the compass with the tip placed at the direction that's on the compass scale - the red line segment points to 45 degrees, so angle θ is 45. We can then represent θ as an x, y coordinate pair if we overlay an x,y Cartesian coordinate system on top of the compass, with its origin (0,0) in the middle of the compass. The x-coordinate for the direction is ax, which is the x-position of the tip of the red arrow - we'll call this the x component. The y-coordinate for the direction is ay, which is the y-coordinate for the tip of the red arrow - we'll call this the y-component. You should be able to see that the red line is the hypotenuse of a right triangle, with ay as one of its legs and ax as the other. We can set the length of a to whatever we want, but it's convenient to use 1 - this makes the compass a unit circle, and it keeps the math as simple as possible. For a right triangle, we know that: sin(θ) = opposite/hypotenuse, which is ax/a We set a equal to 1, so: sin(θ) = ax/1 = ax which means that the sin of θ is the x component. cos(θ) = adjacent/hypotenuse, which is ay/a With a set to 1, this becomes: cos(θ) = ay which means that the cos of θ is the y component. |

We can also calculate θ from ay and ax, because we know that:

tan(θ) = opposite/adjacent = ax/ay

Solving for θ is done by taking the arctangent of each side:

θ = atan(ax/ay)

Armed with this knowledge, to get a mean direction we just need to:

- Calculate the sin of each direction to get x-components

- Calculate the cos of each direction to get y-components

- Calculate an average of the x-components (sin's), and an average of the y-components (cos's)

- Calculate atan(average of sin's/average of cos's) to get the mean angle

Simple, no?

B. Let's calculate the sin of each direction first. Excel has a sin() function built in, but it assumes that our directions are in radians, not degrees.

If you remember from your math

classes, radians are units of distance around the circumference of a unit circle. Since circumference

of a circle is C = 2πr, when the radius (r) is set to 1 the circumference is 2π.

If you remember from your math

classes, radians are units of distance around the circumference of a unit circle. Since circumference

of a circle is C = 2πr, when the radius (r) is set to 1 the circumference is 2π.

If you started at 0 degrees and walked clockwise around a compass, like the one to the left, by the time you got to 90 degrees you would have walked 1/4 of the way around the circle. With a circumference of 2π this is equivalent to 2π/4 = π/2 radians.

Continuing the walk, when you arrive at 180 degrees you would have walked halfway, or 2π/2 = π radians.

By the time you arrive at 270 degrees you would have walked 3/4 of the way, or 3(2π)/4 = 3π/2 radians.

When you arrive at 360 degrees you would have walked 2π radians.

So, there is a one to one correspondence between degrees and radians, and we just need to use Excel's radians() function to do the conversion for us.

- In cell B1 type "Direction in radians"

- In cell B2 type =radians(a2). You'll get an answer of 6.0213... for the first direction of 345

- Copy and paste the value from B2 to B3 through B5 - you will now have the directions in radians for all of the directions in column B

Next we can calculate the sin of these directions in radians:

- Enter "Sin direction" in C1

- Enter =sin(b2) in C2

- Copy and paste C2 to C3 through C5 to get the sin of each direction

Now, this calculation required us to use two columns, the first of which did nothing but convert degrees to radians. We don't need to use the directions in radians in later calculations, so we wouldn't lose anything by doing this unit conversion "on the fly", as part of the sin() calculation.

To do the conversion to radians on the fly, we just need to nest the radians() function inside of the sin() function:

- Enter "Sin direction nested" into cell D1

- Enter =sin(radians(a2)) in D2

- Copy cell D2 to D3 through D5.

You'll see that the numbers in column D and column C are exactly the same, so we were able to do the calculation of the sin of direction without needing to use a column for the unit conversion.

C. In cell E1 enter the label "Cos direction nested", and then enter a formula that calculates cos of each direction, by nesting radians() inside of the cos() function (give this a try, it's just like the sin calculation).

D. Now we need to calculate averages for the sin and cos components of the direction:

- In cell D7 enter the label "Average sin"

- In D8 enter =average(d2:d5) to get the average of the sin column

- Copy and paste this to E8 to get the average of the cos column, and label this calculation "Average cos" in cell E7.

You should get a mean for Sin direction of -0.0603 and for Cos direction of 0.983847.

Note that since we used relative references for the average calculation we could copy D8 and paste it to E8 to get the average of the cos.

We could have used absolute references for the rows for these formulas - that is, if we had used =average(d$2:d$5) it would also have worked - but it wasn't necessary as long as we pasted to the same row that we copied from.

E. To get the mean angle, we need to take the arctangent of the average of the sin's divided by the average of the cos's. The atan() function will return a direction for us, but it will be in radians - we need to use the degrees() function to convert it back. We can nest the atan() function inside of degrees() to get the answer in degrees.

In cell A10 type "Correct average", and in cell A11 type =degrees(atan(d8/e8)).

This should give you an answer of -3.509688

Note that the arctangent function doesn't give a unique solution for all possible combinations of sin and cos, so the final step is:

- If sin(θ) and cos(θ) were both positive, then the answer would already be the mean angle.

- If cos(θ) was negative, then the mean angle would be the arctangent plus 180 degrees (it doesn't matter what sin(θ) is)

- Since sin(θ) is negative and cos(θ) is positive, the mean angle is the answer plus 360 degrees.

Edit the function in A11 to read =360+DEGREES(ATAN(D8/E8)) = 356.49, which is right where it needs to be, close to due north at 360 degrees.

Assignment

This is part 1 of a two part exercise - save your worksheet and save it for part two, which we will do in the next class meeting.