A little binary

We will work today on understanding how the analog properties of the real world are translated into digital representations. Computers have allowed the biological sciences to make huge advances, and have become standard scientific tools. Representing data in a digital form is a basic requirement of using computers. Most of the time this translation from analog to digital doesn't cause problems, but it's important for you to understand that digital representations aren't perfect reproductions, and problems can arise.

To complete the worksheet for today's exercise, you will need to do several things:

- Translate decimal integer numbers to binary

- Express decimal continuous numbers in a floating point format

- Translate letters to ASCII decimal codes, and then to their binary equivalents

1. Translate base 10 numbers to binary numbers.

To understand how binary digits work, it's helpful to think clearly about what a base 10 number, like 20421, actually means. First, each digit in this number is an entry at a "place" - the ones place, 10's place, 100's place, 1000's place, and 10000's place. Each place is a power of 10 - you can see in this table that the powers of 10 are shown, with their decimal equivalent below them. The reason we use powers of 10 is that we have ten digits possible at each place - we can represent any number from 0 to 9 in the 1's place, and to represent 10 we need to enter a 1 in the 10's place.

So, 20,421 is actually:

| Base 10: | 107 | 106 | 105 | 104 | 103 | 102 | 101 | 100 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decimal equivalent | 10000000 | 1000000 | 100000 | 10000 | 1000 | 100 | 10 | 1 | Decimal number: | |

| Base 10 digits | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 20000 + 0 + 400 + 20 + 1 = 20421 |

To represent 20,421 we enter a 2 in the 10000's place, a 0 in the 1000's place, a 4 in the 100's place, a 2 in the 10's place, and a 1 in the 1's place. We then add up each of these numbers to get the decimal number of 20421.

Binary numbers work the same way, but since the only digits we can use are 0 and 1, they are base 2 instead of base 10. This means that the "places" in a binary number are powers of 2 instead of powers of 10.

With base 2, the first position, 20, is equal to 1, just like the 100 position in base 10. But, since we can only use 0's and 1's as digits, we can either have 0 or 1 of these 1's, which means the first position can only represent a 0 or a 1. For numbers bigger than 1 we need to go to the 21 place.

The table below will help you translate decimal numbers into binary. To use it, click on the 0's in the "Binary digits" row to convert them to 1's. Each time you turn a 0 to a 1 the "Decimal equivalent" number is added to the "Decimal number" value.

As a simple example, to convert the decimal number 2 to binary we would need to put a 1 at the 2's place and a 0 at the 1's place, so that the sum is 2+0 = 2.

To fill in the answers for Question 1 on your worksheet, use the converter to find the binary representations for integer numbers from 0 to 10.

| Base 2: | 27 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 20 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decimal equivalent | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | Decimal number: | |

| Binary digits | 0 |

Some help in finding the right pattern of 0's and 1's:

- Start with the biggest decimal equivalent that is smaller than or equal to the number you are converting, and enter a 1. For the first number you're converting (66), 128 is too big and should stay a 0, but 64 is smaller than 66, so it should get a 1.

- Work down the list of decimal equivalents, and if adding the decimal equivalent to 64 either equals or is still less than 66 then put a 1 underneath it.

- Once your decimal number is correct, stop and record the sequence of 0's and 1's on your worksheet as the binary number - this is the binary equivalent to your decimal number.

2. Express decimal numbers in a floating point format. Representing numbers with decimal places on a computer is usually done using floating point numbers. Floating point numbers have a distinct advantage over fixed precision numbers in that numbers of different sizes can be stored in the same floating point variable without excessive loss of information - for example, if we used a fixed level of precision for our decimal numbers, then we would need two digits before the decimal and seven after to store the number 12.3456789, but then if we tried to store the number 0.00000000123456789 it would be truncated at the seventh decimal place as well, which would drop everything but the 0.0000000. With a floating point representation we would represent the first number as 123456789 x 10-7, and the second number as 123456789 x 10-17 - both of these floating point numbers would have all of their significant digits recorded, and we wouldn't have to worry about rounding or truncation changing the data.

Question 2 of your worksheet has several decimal numbers for you to convert to floating point equivalents.

3. Floating point weirdness. As you learned in lecture, we can represent integer numbers exactly with binary equivalents with no loss of accuracy. Even base 10 fractions can't always be accurately represented as decimals - 1/5 is exactly 0.2, but 1/3 is 0.3333 repeating infinitely, and when we express 1/3 as a fraction we have to pick how many digits to retain and round the number at that level. We're used to this issue, know to expect it, and are not generally surprised by it.

This issue is true with base 2 binary numbers as well, but the numbers that can't be perfectly represented as a decimal in binary are different from the ones that can't be perfectly represented as a decimal in base 10. Since Excel needs to convert the base 10 numbers we enter into binary, do the math we ask for on the binary numbers, and then convert back to base 10 we can end up with some weird results, even for very simple calculations we can do in our heads in base 10.

You can see this clearly with a couple of simple examples.

Start excel, and in cell A1 enter "Series". To start, enter two numbers:

- In cell A2 enter 0.01

- In cell A3 enter 0.0099

Cell A3 is thus 0.0001 less than cell A2.

Select cells A2 and A3 and use the fill handle to extend the series to cell A110 (or so...don't fret if you go a little over). This will create a series in which each cell should be 0.0001 less than the one before.

If everything worked as expected, cell A102 should be showing a cell value of 6.07E-17. Computers represent scientific notation this way, so E-17 means "6.07 x 10-17".

What should be in cell A102? If you look at the cell before, A101, it displays the value 0.0001, which is the amount of difference between each row's numbers - which should mean that A102 is calculated by subtracting 0.0001 from 0.0001, and should give you a difference of 0, not 6.07E-17.

The computer seems to recover its senses in the next row - the next cell is formatted as -1E-04 (scientific notation for -0.0001). We would expect A103 to be equal to 0 - 0.0001, so it looks like there was a glitch in cell A102, but then everything went back to normal by the next row.

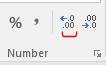

To see what's going on, make column A wider by dragging the right side of the A column heading section to the

right, select cells A2 through A101, and then increase the number of decimals displayed by clicking on the

"Increase Decimal" button,  , until you can see all 15 of the

significant digits that Excel stores. You'll see that although Excel is only displaying the first four decimal

places by default, starting in cell A10 the actual value stored has a digit at the 17th decimal place that

should be 0 but isn't.

, until you can see all 15 of the

significant digits that Excel stores. You'll see that although Excel is only displaying the first four decimal

places by default, starting in cell A10 the actual value stored has a digit at the 17th decimal place that

should be 0 but isn't.

When Excel makes a series, it starts with the two numbers you selected and subtracts the first from the second to decide how much difference there is between cells - it then calculates the next number in the series by adding that difference to the last number currently in the series. To see how much difference Excel thinks there is between the first two cells, in cell B3 enter =A3-A2, and then increase the decimals, and you'll see that Excel thinks that there is a difference of -0.0000999999999999994 instead of -0.0001.

Now that Excel has decided the difference is -0.0000999999999999994 it adds this value to value in A3 to calculate A4, then adds it to the value in A4 to get A5, and so on. With each new value in the series this small error accumulates. Excel rounds these calculations to the fourth digit for display, so the error isn't visible until you get to cell A102, where there are 16 zeros after the decimal place before the first non-zero number, so it displays that number in scientific notation, and you can finally see the result of the errors in the calculations. When cell A103 is calculated the number has a non-zero digit at the 5th decimal place again, so Excel rounds to this level and you can no longer see the calculation error. This makes it look like Excel recovered its senses and fixed the mistake, but the error is still there - it's just concealed again by rounding the number.

Does this matter? Most of the time such a tiny numerical error wouldn't cause problems, but sometimes it does.

For example, in cell B100 enter the formula =0.0002/A100 - this formula divides 0.0002 by the value in cell A100, which is also supposed to be 0.0002, and displays the result as 1. If you increase the decimal places you'll see the value is actually 0.9999999999997, but the error of 0.0000000000003 is tiny, and Excel rounds to the correct value of 1.

Now, copy cell B100 and paste it to cells B101 and B102 you will get the result of dividing 0.0002 by the numbers in cell A101 and A102 respectively. You'll see that everything is still okay for cell B101 (you are dividing 0.0002 by a number that is supposed to be 0.0001, and the result is very close to the correct value of 2 as a result), but in cell B102 you get a massive number of 3294061441733.85. This is because in cell B102 you are dividing 0.0002 by 6.07E-17, instead of dividing 0.0002 by the value of 0 that is supposed to be there. Dividing by 0 should result in an error, since dividing by 0 is undefined mathematically - programmers know to check for division by 0 errors in their programs, and take appropriate steps to avoid problems when they occur. However, dividing by a tiny number is not a problem mathematically, so no error is generated, and a programmer may not thing to check for a value that is mathematically fine, but that is massively incorrect because of a floating point error. These sorts of floating point arithmetic errors can cause problems in the real world (rockets blowing up, for example).

It may seem like the purpose of teaching you this is to make you less trusting of computers, but that's not really the goal - most of the time these sorts of errors are so small that they can be safely ignored. The real take-home message is this: YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR YOUR ANALYSIS! Computers are amazingly useful tools, but converting our base 10, analog world into a computer's base 2 digital world doesn't work perfectly, and even seemingly simple operations can lead to surprising results if you aren't aware of a computer's limitations.

Representing letters, numbers, and symbols using ASCII codes

Computers are able to work with letters and symbols using systems of numeric codes, such as the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) system. ASCII characters are used in the text file format, which is one of the oldest, most universally supported file formats in the world. When the computer recognizes that it is working with a text file, the integer numbers the text file contains are interpreted as codes for letters, symbols, and numbers, and the characters the ASCII codes represent are displayed.

The first 32 ASCII characters are "control" characters that were used to tell old, mechanical printers how to format output, so we will skip over those. The numbering starts at 0, so the first code that represents a punctuation symbol is the number 32, which is a space.

A table of ASCII codes is here:

The DEC column is the ASCII code as a decimal number, Symbol shows the symbol that is being represented, and Description describes the symbol in words.

4. Translate letters to ASCII decimal codes, and then to binary. On your worksheet are several ASCII codes in a table that spells a word (4a on the worksheet). First, use the binary number translator to convert the ASCII code into a binary number, and record it in the Binary number row. Then, look up the ASCII codes in the ASCII table, and record the letter, number, or symbol that corresponds with that code in the Letter row.

Then, for 4c on the worksheet use ASCII characters to spell your first name - remember to capitalize the first letter.

Other systems for encoding information on a computer. I extracted the table, above, from a larger table that included some additional encoding systems - the complete table with all of the encoding systems is here:

Each column is a different way of representing the character in a file - DEC, Symbol, and Description are as before, but there is now a column for octal (OCT), hexadecimal (HEX), binary (BIN), and HTML name and number. Each of these is a different way of representing these characters.

Hexadecimal: the hexadecimal system for example has 16 digits instead of 10 (like base 10) or 2 (like binary). The digits are the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and the letters A, B, C, D, E, and F - the letters are equivalent to 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15 in base 10.

As with base 2 and base 10 the digits are powers of the base, so the first digit is 160 = 1, the second is 161 = 16, the third is 162 = 256, and so on. A hexadecimal number 20 is thus 2 sixteens and 0 ones, or 32. You'll see that the number 42 in decimal is 2A in hexadecimal - that is, 2 sixteens is 32, and A ones is 10, thus 2A is 32 + 10 = 42.

Why is this useful? Since there are 16 digits to work with it's possible to represent big numbers with fewer characters using the hexadecimal system (if you ever watched the movie "The Martian" hexadecimal had its big screen moment - now you know how it works). Again, as long as the computer knows that the characters are hexadecimals it can properly interpret them.

Answer question 4d based on your understanding of hexadecimal numbers.

HTML: the hypertext markup language (HTML) is used for web pages (including this one). HTML formatted files can use numeric or text codes to indicate numbers, letters, and symbols as well. Web browsers know how to interpret the HTML codes, and convert them appropriately when the page is displayed. The advantage of HTML over pure ASCII is that HTML has information about how to format the document. Formatting instructions are provided using tags - tags are enclosed in < and > characters, and there are opening and closing tags are paired together with content between them. For example, if you were to open this page in a text editor (like the Windows notepad program) this paragraph would look like this:

<p><strong>HTML:</strong> the hypertext markup language (HTML) is used for... </p>

The opening and closing tags, <p> and </p>, identify this as a paragraph, and the web browser applies the font, alignment, and spacing before and after the paragraph that I've specified for paragraph content. The <strong> and </strong> tags indicate that the first word, HTML:, should be in boldface. A text editor doesn't know to interpret the tags as formatting instructions, so if you open an HTML file in a text editor all of the tags are just displayed as though they are regular file content. A web browser that supports HTML formatted files knows how to interpret the tags, and rather than displaying the tags it uses them for formatting information, and only the content within the tags is displayed.

So, even though computers are only able to understand 0 and 1, there are various coding systems that allow computers to use strings of 0 and 1 to represent numbers, letters, and symbols.

Answer questions 4e and 4f based on your understanding of HTML.

That's it for today - we'll work with digital representation of color and sound next time.